What is the History of the Temple of Olympian Zeus?

The Temple of Olympian Zeus, also known as the Olympieion, is a monumental temple in Athens, Greece. It was dedicated to Zeus, the king of the Olympian gods. Construction began in the 6th century BC during the rule of the Athenian tyrants. According to Pausanias in his work “Description of Greece,” the temple’s construction started under the tyrant Peisistratos but wasn’t completed until the 2nd century AD under Roman Emperor Hadrian.

How Did the Construction of the Temple Begin?

The temple is located about 0.3 miles southeast of the Acropolis and 0.4 miles south of Syntagma Square. It was built on the site of an ancient sanctuary dedicated to Zeus. As Herodotus mentioned, an earlier temple was constructed by the tyrant Peisistratos around 550 BC. His sons, Hippias and Hipparchos, initiated the construction of a new, larger temple around 520 BC, designed by the architects Antistates, Callaeschrus, Antimachides, and Phormos. This information is confirmed by Vitruvius in his treatise “De Architectura.”

Why Was the Temple Unfinished for So Long?

The construction halted when the tyranny was overthrown, and Hippias was expelled in 510 BC. According to Aristotle in “Politics,” the unfinished state of the temple was likely due to the Greeks considering it hubris to build on such a grand scale. Only the platform and some column elements were completed, leaving the temple unfinished for 336 years. This prolonged halt is noted by Thucydides in his “History of the Peloponnesian War.”

How Was the Project Revived and Completed?

In 174 BC, Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes revived the project. The Roman architect Decimus Cossutius redesigned the temple to feature three rows of eight columns at the front and back and a double row of twenty on the sides, totaling 104 columns. The columns stood 56 feet high and 6 feet 7 inches in diameter. The building material switched to high-quality Pentelic marble, and the architectural order changed from Doric to Corinthian. According to Strabo in his “Geographica,” the project halted again with Antiochus’ death in 164 BC. It wasn’t until Hadrian’s reign in the 2nd century AD that the temple was finally completed. During Hadrian’s visit to Athens in 124-125 AD, a massive building program began, including the completion of the Temple of Olympian Zeus. The temple was formally dedicated by Hadrian in 132 AD, as recorded by Cassius Dio in “Roman History.”

What Happened to the Temple in Later Years?

The temple was damaged during the sack of Athens by the Heruli in 267 AD, and likely never repaired, as mentioned by Pausanias. It suffered further destruction from a 5th-century earthquake. Over the centuries, it was systematically quarried for building materials. By the end of the Byzantine period, only 21 of the original 104 columns remained. Today, fifteen columns stand, and a sixteenth lies on the ground, having fallen during an 1852 storm. This extensive quarrying during the Byzantine era is also noted by Procopius in “Buildings.”

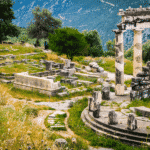

How is the Temple Viewed Today?

Today, the Temple of Olympian Zeus is a crucial part of Athens’ archaeological heritage. It remains a testament to ancient Greek and Roman engineering prowess, symbolizing Athens’ storied past. As noted by the Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens, preservation efforts continue to maintain this historic site.

Key Points

- Location: Central Athens, Greece

- Construction Started: 6th century BC

- Completed: 2nd century AD under Roman Emperor Hadrian

- Original Columns: 104

- Remaining Columns: 16

- Height of Columns: Approximately 55 feet (17 meters)

- Significance: Largest temple in ancient Greece during the Roman period

Recent Information

In recent years, efforts to preserve and maintain the site have been ongoing. According to the Greek Ministry of Culture, the temple remains a critical part of Athens’ rich historical and cultural heritage, with archaeological research and conservation projects ensuring its legacy endures for future generations.

Access Information

The Temple of Olympian Zeus is easily accessible by metro, bus, or on foot from downtown Athens. Metro Line 2 (red line) to “Akropoli” station or Line 1 (green line) to “Thissio” station brings you within a 10-minute walk. Several bus lines, including 035, 106, 126, and others, stop near the site. Walking from central locations like Syntagma Square is also a convenient option.

Tickets and Opening Hours

As of 2024, the temple is open daily except for major public holidays. During summer (April to October), it operates from 8:00 am to 8:00 pm. In winter (November to March), the hours are 8:30 am to 3:00 pm. Tickets cost $7 for adults and $3.50 for students and seniors over 65. Children under 18 and individuals with disabilities can enter for free. It is recommended to check the official website for any updates before visiting.

How Was the Temple of Olympian Zeus Excavated?

The Temple of Olympian Zeus has undergone several excavation efforts over the years. British archaeologist Francis Penrose, noted for his work on the Parthenon, led the first major excavation from 1889 to 1896. According to historical records, Penrose’s work uncovered significant portions of the temple’s structure and layout. In 1922, German archaeologist Gabriel Welter continued the excavation, focusing on the surrounding area and contributing further to our understanding of the temple’s historical context. In the 1960s, Greek archaeologists, led by Ioannes Travlos, conducted additional excavations, which provided more insights into the temple’s construction and usage. Today, the Ephorate of Antiquities under the Greek Interior Ministry manages the temple and its surrounding ruins.

What is the Current State of the Temple?

The Temple of Olympian Zeus is now an open-air museum and is part of the unified archaeological sites of Athens. The Ephorate of Antiquities protects and supervises the historical site. Visitors can explore the temple ruins and appreciate the grandeur of ancient Greek architecture. As highlighted in the Greek Interior Ministry’s reports, ongoing conservation efforts ensure the site’s preservation for future generations.

What Was the Significance of Mythodea 2001?

On June 28, 2001, renowned composer Vangelis organized the Mythodea concert at the Temple of Olympian Zeus. According to concert records, the event was linked to NASA’s Mars mission and featured famous sopranos Jessye Norman and Kathleen Battle. The concert drew thousands of spectators, both inside and outside the temple grounds. The London Metropolitan Orchestra and the Greek National Opera also participated, creating a grand spectacle. Broadcast by 20 television networks worldwide, the event combined music with visuals of ancient Greek art and the planet Mars, offering a unique cultural experience.

How Did the 2007 Ellinais Ceremony Honor Zeus?

On January 21, 2007, a group of Greek pagans conducted a ceremony at the temple to honor Zeus. As noted by Ellinais, the organization that advocates for the recognition of ancient Greek religious practices, this event marked a significant moment for modern practitioners. In 2006, Ellinais won a court battle to gain recognition for these ancient practices. The ceremony at the Temple of Olympian Zeus was a symbolic reaffirmation of these traditions and highlighted the temple’s enduring cultural significance.

What Makes the Temple of Olympian Zeus a Must-Visit?

The Temple of Olympian Zeus is a significant historical and cultural landmark in Athens. Its long construction history and numerous excavations reveal much about ancient Greek and Roman architecture. As noted by the Greek National Tourism Organization, the temple’s current role as an open-air museum allows visitors to connect with Greece’s rich heritage. Events like Mythodea 2001 and the Ellinais ceremony underscore the temple’s ongoing cultural importance, making it a must-visit for anyone interested in history and ancient architecture.

Additional Information from Recent Years

In recent years, there have been continued efforts to preserve and promote the Temple of Olympian Zeus. The site remains a popular tourist destination in Athens, attracting scholars, history enthusiasts, and visitors from around the world. According to recent reports, efforts to enhance visitor experiences include improved signage, guided tours, and interactive exhibits. These initiatives aim to provide a deeper understanding of the temple’s historical and cultural context, ensuring that its legacy endures for future generations.

Who Was Zeus and What Did He Represent?

Zeus, known as the king of the gods, was the god of the sky, lightning, thunder, law, and order in ancient Greek religion. His name is similar to the first part of his Roman counterpart, Jupiter. According to Hesiod’s Theogony, Zeus was the youngest child of Cronus and Rhea. Although the youngest, some myths consider him the eldest because his siblings were disgorged by Cronus after Zeus’s birth. As noted by ancient texts, Zeus’s dominion over the sky made him a prominent deity in the Greek pantheon, symbolizing power and authority.

What Ancient Texts Confirm Zeus’s Dominion Over the Sky?

Several ancient texts confirm Zeus’s dominion over the sky, symbolizing his power and authority:

- Hesiod’s Theogony: This epic poem details the genealogy of the gods and describes Zeus as the ruler of the sky after overthrowing his father, Cronus.

- Homer’s Iliad: Throughout this epic, Zeus is frequently referred to as the king of the gods who controls the weather and presides over the heavens.

- Homeric Hymns: These ancient hymns often highlight Zeus’s authority over the sky and other gods.

- Pausanias’s “Description of Greece”: Pausanias mentions Zeus’s role as the king of the gods and his dominion over the sky.

Who Were Zeus’s Family and Offspring?

Zeus was typically married to Hera. Their children included:

- Ares

- Eileithyia

- Hebe

- Hephaestus

At the oracle of Dodona, his consort was Dione, with whom he fathered Aphrodite (Iliad). According to the Theogony, his first wife was Metis, and they had Athena. Zeus’s numerous affairs led to many divine and heroic offspring, such as:

- Apollo

- Artemis

- Hermes

- Persephone

- Dionysus

- Perseus

- Heracles

- Helen of Troy

- Minos

- The Muses

How Was Zeus Viewed by Other Gods and Cultures?

Zeus was respected as the chief deity, often referred to as the “Sky Father.” Other gods, even those not his direct offspring, addressed him as Father. Pausanias noted, “That Zeus is king in heaven is a saying common to all men.” Zeus was equated with various weather gods from different cultures, and his symbols included the thunderbolt, eagle, bull, and oak. His image and traits also drew from ancient Near Eastern cultures, reflecting a blend of influences that shaped his worship and representation.

What Are Some Names and Epithets of Zeus?

The name Zeus in Greek is Ζεύς (Zeús), with different grammatical forms for various cases (e.g., Δία for accusative). Zeus’s name is derived from the Proto-Indo-European god of the daytime sky, Dyeus. This connection is seen in related deities like the Vedic Dyaus and the Latin Jupiter. The earliest forms of Zeus’s name appear in Linear B script as di-we and di-wo.

How Is Zeus’s Name Interpreted?

Plato suggested a folk etymology, linking Zeus’s name to life and cause, but this is not supported by modern scholarship (Cratylus). Diodorus Siculus mentioned Zeus being called Zen because he was seen as the cause of life. Lactantius noted that Zeus’s name came from being the first to live among Cronus’s children.

What Are Zeus’s Other Names?

Zeus had many epithets, reflecting his various roles and the local gods he absorbed. These epithets were more than just names; they signified his many aspects and the diverse worship he received across different regions. Some of his epithets included:

- Zeus Olympios (of the Olympian games)

- Zeus Xenios (protector of guests and hospitality)

- Zeus Horkios (keeper of oaths)

- Zeus Panhellenios (of all Greeks)

These titles illustrate the widespread reverence for Zeus and his integral role in Greek mythology and religion.

Where Was Zeus Born According to Greek Mythology?

Zeus, the king of the gods in Greek mythology, has several birthplaces attributed to him in various myths. Here are the most prominent ones:

Where Did Hesiod Say Zeus Was Born?

According to Hesiod’s Theogony (circa 700 BC), Rhea gave birth to Zeus in Lyctus, Crete. To protect him from his father Cronus, she hid him in a cave on Mount Aegaeon. Cronus had been swallowing all his children at birth, fearing a prophecy that one would overthrow him. Rhea tricked Cronus by giving him a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes, which he swallowed, believing it to be Zeus (Hesiod, Theogony, lines 468-484).

What Other Locations Are Mentioned as Zeus’s Birthplace?

Various other sources offer different locations for Zeus’s birthplace:

- Eumelos of Corinth: Believed Zeus was born in Lydia, as noted by John the Lydian (De Mensibus, IV).

- Callimachus: In his Hymn to Zeus, Callimachus states that Zeus was born in Arcadia (Callimachus, Hymn to Zeus, line 8).

- Diodorus Siculus: Initially mentions Mount Ida but later states Zeus was born in Dicte (Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, Book 5, Chapter 70).

- Apollodorus: Claims Zeus was born in a cave in Dicte (Apollodorus, Bibliotheca, 1.1.6).

These differing accounts reflect the rich and varied oral traditions in ancient Greece. Each region sought to associate itself with the chief of the gods, enhancing its cultural and religious significance.

How Did Zeus Escape Being Swallowed by Cronus?

According to the myth, Rhea, Zeus’s mother, sought help from Gaia and Uranus. They devised a plan to save Zeus. Rhea gave birth to Zeus in secret and handed Cronus a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes. Cronus, thinking it was his son, swallowed the stone. This act allowed Zeus to grow up safely and eventually fulfill the prophecy by overthrowing Cronus (Theogony, lines 485-491).

What Happened After Zeus’s Birth?

Zeus was raised in a cave on Mount Aegaeon by Gaia. Some myths say nymphs or even animals helped care for him. As he grew, Zeus prepared to challenge Cronus and free his siblings. This act marked the beginning of his rise to power as the chief deity of Greek mythology (Apollodorus, Bibliotheca, 1.1.7).

Who Were Zeus’s Family and Offspring?

Who Are Zeus’s Siblings?

Zeus’s siblings, who were also swallowed by Cronus and later freed, include:

- Hestia

- Demeter

- Hera

- Hades

- Poseidon

These gods and goddesses became significant figures in Greek mythology, ruling various aspects of the world and human life (Hesiod, Theogony, lines 453-506).

Who Were Zeus’s Offspring?

Zeus was typically married to Hera. Their children included:

- Ares

- Eileithyia

- Hebe

- Hephaestus

At the oracle of Dodona, his consort was Dione, with whom he fathered Aphrodite. According to the Theogony, his first wife was Metis, and they had Athena. Zeus’s numerous affairs led to many divine and heroic offspring, such as:

- Apollo

- Artemis

- Hermes

- Persephone

- Dionysus

- Perseus

- Heracles

- Helen of Troy

- Minos

- The Muses (Hesiod, Theogony, lines 886-900).

What Are Some Common Symbols Associated with Zeus?

Zeus is often depicted with symbols that highlight his power and dominion over the sky and thunder:

- Thunderbolt

- Eagle

- Bull

- Oak tree (Pausanias, Description of Greece, 1.24.6).

How Is Zeus Related to Other Weather Gods?

Zeus’s role as the sky and thunder god links him to similar deities in other Indo-European cultures. His name and attributes share common origins with gods like the Vedic Dyaus Pita and the Roman Jupiter. This connection underscores Zeus’s ancient roots and widespread worship across different cultures (Walter Burkert, Greek Religion).

What Are Some Epithets of Zeus?

Zeus was known by many epithets, each reflecting a different aspect of his power and influence. These epithets highlight his roles in various aspects of life and his dominion over different spheres.

Zeus Olympios

As Zeus Olympios, he was revered as the king of the gods and the ruler of Mount Olympus. This title emphasizes his supreme authority among the gods and his overarching rule over the universe. According to Pausanias in his “Description of Greece,” this epithet signifies Zeus’s position as the paramount deity worshipped in grand temples, such as the one at Olympia.

Zeus Xenios

Zeus Xenios reflects his role as the protector of guests and hospitality. This title underscores the importance of hospitality in ancient Greek culture, where Zeus was believed to oversee and safeguard the sacred bond between host and guest. As noted by Homer in the “Odyssey,” Zeus Xenios ensured that proper respect and kindness were extended to all visitors.

Zeus Horkios

In the capacity of Zeus Horkios, he was the keeper of oaths. This aspect of Zeus underscores his role in ensuring that promises and vows were upheld. Hesiod’s “Works and Days” references Zeus Horkios as the enforcer of moral and ethical conduct, punishing those who broke their solemn promises.

Zeus Agoraeus

Zeus Agoraeus was the guardian of public assemblies and markets. This epithet highlights his influence over civic life and the proper functioning of commerce and social gatherings. According to inscriptions found in ancient agoras, Zeus Agoraeus was invoked to maintain order and fairness in public dealings and trade.

How Is Zeus’s Name Derived?

Zeus’s name has a clear Indo-European origin, linked to the Proto-Indo-European god of the daytime sky, *Dyeus. This connection underscores Zeus’s ancient roots and widespread worship across different cultures. As explained by Walter Burkert in “Greek Religion,” the name Zeus is derived from the root *dyeu- meaning “to shine,” which is also the root for “sky” and “day” in various Indo-European languages. This etymology reflects Zeus’s dominion over the sky and his association with brightness and authority.

What Are the Symbols of Zeus?

Zeus is often depicted with symbols that highlight his power and dominion over the sky and thunder:

- Thunderbolt: This is his most famous attribute, symbolizing his control over lightning and storms.

- Eagle: Representing his role as the king of the gods and his ability to see all from above.

- Bull: Reflecting his strength and virility, often associated with fertility rites.

- Oak tree: Sacred to Zeus, symbolizing strength and endurance.

Where Did Zeus Spend His Infancy?

Zeus’s infancy is depicted with great detail in various mythological accounts. Hesiod in his “Theogony” mentions Zeus growing up swiftly after his birth in a cave in Crete. Apollodorus adds that Rhea handed baby Zeus to the nymphs Adrasteia and Ida, who nursed him with the milk of the she-goat Amalthea. The Kouretes guarded the cave, making noise with their shields to mask Zeus’s cries from Cronus.

According to Diodorus Siculus, Rhea gave birth to Zeus on Mount Ida and entrusted him to the Kouretes. They raised him with honey and milk from Amalthea. The Kouretes created loud noises to deceive Cronus, and Diodorus notes that Zeus’s umbilical cord fell off at the river Triton.

How Did Zeus’s Siblings Avoid Cronus’s Wrath?

Hyginus provides a unique account, stating that Cronus cast Poseidon into the sea and Hades into the Underworld instead of swallowing them. When Zeus was born, Hera asked Rhea for him. Rhea tricked Cronus with a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes, which Cronus swallowed. Hera then gave Zeus to Amalthea, who hid him by hanging his cradle from a tree, making him unfindable by Cronus.

Hyginus also mentions that Ida, Althaea, and Adrasteia, sometimes considered daughters of Oceanus, were Zeus’s nurses. According to a fragment by Epimenides, the nymphs Helike and Kynosura nursed Zeus. To hide from Cronus, Zeus transformed into a snake, and his nurses turned into bears.

Who Else Nursed Baby Zeus?

Musaeus states that Rhea gave Zeus to Themis, who then handed him to Amalthea. Antoninus Liberalis offers a unique account where Rhea gave birth to Zeus in a sacred cave filled with bees. Thieves attempting to steal honey saw Zeus’s swaddling clothes, their armor broke, and Zeus would have killed them if not for the intervention of the Moirai and Themis. Instead, he turned them into birds.

These accounts highlight the myths surrounding Zeus’s early life, involving hiding, deception, and transformation to protect him from Cronus. Raised by nymphs and protected by various guardians, Zeus’s early years set the stage for his eventual rise as the king of the gods. The myths reflect the ancient Greeks’ fascination with divine birth and protection, illustrating Zeus’s destined greatness from birth.

How Did Zeus Ascend to Power?

According to Hesiod’s Theogony, Zeus’s rise to power begins after he reaches adulthood. Cronus is forced to disgorge Zeus’s siblings and the stone through the stratagems of Gaia and Zeus’s strength. Zeus then places the stone at Delphi as a sign for mortals. After this, Zeus frees the Cyclopes, who gift him his thunderbolt in gratitude. Hesiod writes, “Zeus set that stone in the wide-pathed earth at Pytho, the prophetic Delphi, to be a sign thenceforth and a marvel to mortal men” (Theogony 498-500).

What Was the Titanomachy?

The Titanomachy, or the War of the Titans, was a ten-year conflict between the Olympians, led by Zeus, and the Titans, led by Cronus. The Olympians fought from Mount Olympus, while the Titans fought from Mount Othrys. The battle remained undecided until Zeus, following Gaia’s advice, released the Hundred-Handers. These giants helped Zeus by hurling massive rocks at the Titans. Zeus launched a final attack with his thunderbolts, leading to the Titans’ defeat. Hesiod describes this climactic battle in Theogony, lines 617-735.

How Did Metis Contribute to Zeus’s Victory?

Apollodorus provides an account in his Bibliotheca, which details how Zeus enlisted the help of Metis, an Oceanid. Metis gave Cronus an emetic potion, forcing him to disgorge Zeus’s siblings and the stone. Zeus then waged war against the Titans for ten years. Following Gaia’s prophecy, Zeus released the Cyclopes and the Hundred-Handers from Tartarus, killing their guard, Campe. The Cyclopes gave Zeus his thunderbolt, Poseidon his trident, and Hades his helmet of invisibility. Together, they defeated the Titans. Apollodorus writes, “On the advice of Gaia, they released the Hundred-Handers and the Cyclopes from their bonds, and they, out of gratitude, gave Zeus thunder and lightning and a thunderbolt” (Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.2.1).

How Was the World Divided Among Zeus and His Brothers?

According to the Iliad, after defeating the Titans, Zeus shared the world with his brothers by drawing lots. Zeus received the sky, Poseidon got the sea, and Hades took the underworld. The earth and Mount Olympus were left as common ground for all gods. Homer writes, “He (Zeus) won the bright air and the clouds, and the sky; Poseidon won the sea’s grey surf; Hades had the black land of death” (Iliad 15.187-193).

Key Points

Stone of Delphi: Zeus places the disgorged stone at Delphi as a sign for mortals.

Thunderbolt: Gifted by the Cyclopes, symbolizing Zeus’s power.

Titanomachy: A ten-year war between Olympians and Titans for control of the universe.

Hundred-Handers: Giants who helped Zeus defeat the Titans.

Division of Realms: Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades shared the cosmos through drawing lots.

Zeus’s ascension highlights his strategic thinking, powerful alliances, and ultimate victory over the Titans, solidifying his role as the king of the gods.

How Did Zeus Overcome Challenges to His Power?

What Was the Gigantomachy?

When Zeus became the king of the cosmos, his rule faced immediate threats. One major challenge was the Gigantomachy, a battle between the Olympian gods and the Giants. Apollodorus provides a detailed account: the Giants were born from Gaia, who was angry at Zeus for imprisoning the Titans. A prophecy claimed that the Giants could only be defeated with the help of a mortal. Gaia sought a special herb to protect the Giants, but Zeus ordered Eos, Selene, and Helios to stop shining and harvested all the herbs himself. He then summoned Heracles to aid in the battle.

During the conflict, Porphyrion, one of the strongest Giants, attacked Heracles and Hera. Zeus struck Porphyrion with a thunderbolt just as he was about to assault Hera, allowing Heracles to kill him with an arrow (Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.6.1-2).

How Did Zeus Defeat Typhon?

After the Gigantomachy, Zeus faced another challenge from Typhon, a monstrous serpentine giant. In Hesiod’s “Theogony,” Typhon, born from Gaia and Tartarus, had a hundred snaky, fire-breathing heads. Typhon aimed to overthrow Zeus. Zeus quickly defeated him in a catastrophic battle, hurling Typhon down to Tartarus with his thunderbolt (Hesiod, Theogony, lines 820-880).

Apollodorus offers a more elaborate version. Typhon attacked heaven, causing the gods to flee to Egypt. Zeus fought Typhon with his thunderbolt and sickle but was overpowered and had his sinews torn out. Typhon took Zeus to the Corycian Cave, but Hermes and Aegipan stole back Zeus’s sinews, reviving him. Zeus pursued Typhon to Mount Nysa, where the Moirai weakened Typhon with ephemeral fruits. Zeus finally crushed Typhon under Mount Etna (Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.6.3).

Nonnus adds that Cadmus and Pan retrieved Zeus’s sinews by luring Typhon with music and tricking him (Dionysiaca, Book 2).

What Was the Attempted Overthrow by Other Olympians?

In Homer’s Iliad, Hera, Poseidon, and Athena conspired to overthrow Zeus. They planned to bind him, but Thetis summoned Briareus, one of the Hecatoncheires. His presence caused the conspirators to abandon their plan (Homer, Iliad, Book 1, lines 396-406).

How Did Zeus Maintain His Rule?

Zeus faced many threats to his rule, from the Gigantomachy and Typhon to conspiracies among the Olympians. He used strategy, allies, and sheer power to overcome these challenges. His ability to enlist the help of mortals and other gods played a crucial role in maintaining his supremacy. These myths show Zeus’s central role in Greek mythology as the ultimate ruler of gods and men.

Who Were the Seven Wives of Zeus?

Who Was Metis and What Happened to Her?

Zeus’s first wife was Metis, one of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, according to Hesiod’s Theogony (lines 886–900). When she was about to give birth to Athena, Zeus swallowed her whole on the advice of Gaia and Uranus to prevent a prophecy that her son would overthrow him. Athena later emerged from Zeus’s head, fully grown and armored.

What Is the Story of Zeus and Themis?

Zeus’s second wife was Themis, a Titaness and daughter of Uranus and Gaia, as noted in Hesiod’s Theogony (lines 901–906). With Themis, Zeus fathered the Horae, who represented the natural order: Eunomia (Good Order), Dike (Justice), and Eirene (Peace), and the three Moirai (Fates): Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos.

Who Was Eurynome and What Did She Give Zeus?

Eurynome, another Oceanid, was Zeus’s third wife, according to Hesiod’s Theogony (lines 907–911). Together, they had the Charites, or Graces: Aglaea (Splendor), Euphrosyne (Joy), and Thalia (Good Cheer).

What Was Zeus’s Relationship with Demeter?

Demeter, Zeus’s sister, became his fourth wife. Their union produced Persephone, who later became the queen of the underworld, as mentioned in Hesiod’s Theogony (line 912).

Who Was Mnemosyne and What Were Her Children?

Mnemosyne, the Titaness of memory, was Zeus’s fifth wife. Hesiod’s Theogony (lines 915–917) describes how Zeus lay with her for nine nights, and she bore him the nine Muses, goddesses of the arts: Calliope, Clio, Erato, Euterpe, Melpomene, Polyhymnia, Terpsichore, Thalia, and Urania.

Who Were the Children of Zeus and Leto?

Leto was Zeus’s sixth consort. According to Hesiod’s Theogony (lines 918–920), she bore him the twins Apollo and Artemis, who became major deities in the Greek pantheon. Apollo was the god of the sun, music, and prophecy, while Artemis was the goddess of the hunt and the moon.

How Did Hera Become Zeus’s Final Wife?

Hera, Zeus’s sister, was his seventh and final wife. Hesiod’s Theogony (lines 921–923) mentions that they had several children together, including Ares, the god of war; Hebe, the goddess of youth; and Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth. This union solidified Hera’s role as the queen of the gods.

Conclusion

Zeus’s marriages and numerous offspring illustrate the complex relationships and mythological tales central to ancient Greek religion. His unions with these goddesses produced many significant deities and figures in Greek mythology, each playing vital roles in the ancient world’s religious and cultural narratives. These accounts and interpretations are supported by multiple ancient sources, including Hesiod, Apollodorus, and various classical authors, who offer a rich tapestry of narratives and traditions surrounding Zeus’s life and significance.

What is the Story of Zeus and Hera’s Marriage?

How Did Zeus and Hera’s Relationship Begin?

Zeus’s relationship with Hera has many versions in ancient mythology. According to Hesiod’s Theogony (lines 921–923), Hera was Zeus’s seventh and final wife. They had three children: Ares, Hebe, and Eileithyia. However, other accounts suggest different beginnings for their relationship. Homer in the Iliad mentions that Zeus and Hera first lay together before Cronus was sent to Tartarus, without their parents’ knowledge.

What Myths Describe Their Marriage?

According to Eustathius, the commentator of the Iliad, Oceanus and Tethys gave Hera to Zeus in marriage after the exile of Cronus. Shortly after their marriage, Hera gave birth to Hephaestus, claiming she bore him on her own to conceal her previous union with Zeus on the island of Samos. Callimachus, in his “Aetia,” claims that Zeus stayed with Hera for three hundred years on Samos.

What Is the Cuckoo Bird Story?

According to a scholion on Theocritus’ Idylls, Zeus transformed into a cuckoo bird during a storm to seduce Hera. She found the bird on Mount Thornax, took pity on it, and covered it with her cloak. Zeus then transformed back and took hold of her, promising to make her his wife when she resisted. Pausanias also refers to this myth, identifying the location as Mount Thornax.

How Did Zeus and Hera’s Wedding Occur?

Plutarch, as recorded by Eusebius in his Praeparatio Evangelica, says that Zeus kidnapped Hera and took her to Mount Cithaeron, where they found a natural bridal chamber. When Macris looked for Hera, Cithaeron claimed Zeus was with Leto. In another version, Hera hid in a cave to avoid Zeus until an earthborn man named Achilles convinced her to marry him. Stephanus of Byzantium and Callimachus in Aetia mention the union occurring at Hermione and Naxos, respectively.

What gifts were given at their wedding?

Authors such as Eratosthenes and Hyginus, citing Pherecydes, mention gifts at the wedding of Zeus and Hera. According to Eratosthenes, Gaia gave a tree that produced golden apples as a wedding gift, which were planted in the “garden of the gods” near Mount Atlas. A commentator on Apollonius of Rhodes’ Argonautica also confirms this event. According to Diodorus Siculus, the wedding took place near the river Theren in Knossos. Lactantius attributes the wedding location to Samos.

How Did Zeus Reconcile with Hera?

Pausanias recounts that when Hera was angry with Zeus, she retreated to Euboea. Zeus, unable to resolve the situation, sought advice from Cithaeron, who instructed him to fashion a wooden statue and pretend to marry “Plataea,” a daughter of Asopus. Hera, upon discovering the ruse, reconciled with Zeus. Plutarch’s version, recorded by Eusebius, states that Hera retreated to Cithaeron, and Zeus, with Alalcomeneus’s help, created a wooden bride named Daidale, leading to a joyful reconciliation.

Conclusion

Zeus and Hera’s marriage, filled with deception, reconciliation, and divine intervention, reflects the complexities of their relationship in Greek mythology. Various ancient sources, including Hesiod, Homer, Callimachus, and others, provide rich and diverse narratives that highlight the dynamics between these two prominent deities.

What Are the Myths Surrounding Zeus’s Affairs?

Zeus, despite being married to Hera, is infamous for his numerous affairs with mortal women. Various ancient texts describe these relationships, often involving Zeus transforming himself into different forms to seduce or deceive his lovers.

What Forms Did Zeus Take During His Affairs?

In many myths, Zeus changes his form to pursue his lovers:

Europa: According to a scholion on the Iliad, citing Hesiod and Bacchylides, Zeus transforms into a bull to lure Europa. While she picks flowers with her companions in Phoenicia, he takes her to Crete and reveals his true form (Hesiod, Theogony and Bacchylides, Odes).

Leda: In Euripides’ Helen, Zeus becomes a swan and, being chased by an eagle, finds refuge in Leda’s lap, seducing her (Euripides, Helen).

Antiope: In Euripides’ lost play Antiope, Zeus takes the form of a satyr to sleep with her (Euripides, Antiope).

Callisto: According to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Zeus seduces Callisto in the form of Artemis. Apollodorus mentions he took Apollo’s form (Ovid, Metamorphoses; Apollodorus, Bibliotheca).

Alcmene: Pherecydes states Zeus impersonates Amphitryon, Alcmene’s husband, to seduce her (Pherecydes, Histories).

Danae: Zeus approaches Danae as a shower of gold, impregnating her (Ovid, Metamorphoses).

Aegina: Ovid also describes Zeus abducting Aegina as a flame (Ovid, Metamorphoses).

How Did Hera React to Zeus’s Affairs?

Hera, Zeus’s wife, is often depicted as jealous and vengeful towards Zeus’s lovers and their offspring:

Io: Hera transforms Io into a cow. Apollodorus says Hera sends a gadfly to torment Io, driving her to Egypt (Apollodorus, Bibliotheca).

Semele: Hera tricks Semele into asking Zeus to appear in his divine form. Semele perishes from the sight (Callimachus, Hymns).

Callisto: Callimachus narrates that Hera turns Callisto into a bear and has Artemis shoot her (Callimachus, Hymns).

Heracles: Hera persecutes Heracles throughout his life, even though he is Zeus’s son by Alcmene (Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica).

What Ended Zeus’s Affairs with Mortals?

Diodorus Siculus claims that after fathering Heracles with Alcmene, Zeus stopped having affairs with mortal women. He ceased begetting humans and fathered no more children (Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica).

These stories of Zeus’s affairs and Hera’s responses reflect the complexities of divine relationships in Greek mythology and highlight Zeus’s central role in many myths.

Prometheus and Conflicts with Humans

What Trick Did Prometheus Play on Zeus?

Prometheus tricked Zeus to benefit humans. At Mecone, where gods met to discuss sacrifices, Prometheus divided a sacrificial ox into two portions. He covered the meat and fat with the ox’s stomach, while he dressed the bones with fat. When Zeus chose the pile of bones, this set the precedent for humans keeping the meat and fat while offering bones to the gods. This tale is detailed in Hesiod’s Theogony (lines 535-557).

How Did Zeus React to Prometheus’s Trick?

Zeus, angered by Prometheus’s deception, banned humans from using fire. However, Prometheus stole fire from Olympus and gave it to humans, as mentioned in Hesiod’s Theogony (lines 565-570). Enraged further, Zeus punished Prometheus by chaining him to a cliff, where an eagle ate his liver daily, and it regenerated every night. This punishment is vividly described in Hesiod’s Works and Days (lines 47-105).

What Was Zeus’s Punishment to Humanity?

Zeus decided to punish humans by creating Pandora, the first woman, described as a “beautiful evil.” He ordered Hephaestus to mold her from earth, and other gods contributed to her creation, bestowing her with various traits. Hermes named her Pandora. She was given in marriage to Epimetheus, Prometheus’s brother, with a jar containing many evils. When Pandora opened the jar, she released all the evils into the world, but hope remained inside, as recounted in Hesiod’s Works and Days (lines 60-105).

How Did Zeus Respond to Human Wickedness?

Appalled by human sacrifices and decadence, Zeus decided to wipe out mankind with a great flood. With Poseidon’s help, he flooded the world, sparing only Deucalion and Pyrrha. This flood narrative appears in various ancient texts, highlighting Zeus’s control and judgment over humanity, notably in Apollodorus’s Library (1.7.2).

These narratives demonstrate Zeus’s complex relationship with humanity, reflecting both his authority and the moral lessons imparted through Greek mythology.

Zeus in the Iliad

How Does Zeus Influence the Events in the Iliad?

Zeus plays a significant role in Homer’s Iliad, influencing the outcome of the Trojan War through various interventions and decisions.

What Are Some Key Scenes Involving Zeus?

Book 2: Zeus sends Agamemnon a dream, partially controlling his decisions. This dream persuades Agamemnon to launch a massive assault on Troy.

Book 4: Zeus assures Hera that he will ultimately destroy Troy, despite his neutral stance, highlighting the inevitability of Troy’s fall.

Book 7: Zeus, along with Poseidon, ruins the Achaeans’ fortifications, demonstrating his power over both gods and mortals.

Book 8: Zeus forbids other gods from intervening in the war and returns to Mount Ida to contemplate his decision that the Greeks will lose.

Book 14: Hera seduces Zeus, distracting him to aid the Greeks. This scene showcases Hera’s cunning and Zeus’s vulnerability.

Book 15: Zeus wakes to find Poseidon helping the Greeks. So, he sends Hector and Apollo to aid the Trojans. This reinforces the theme of divine influence on humans.

Book 16: Zeus is upset by Sarpedon’s death. But he cannot intervene without contradicting his earlier decisions. This shows that even gods have limits.

Book 17: Zeus is emotionally affected by Hector’s fate, adding depth to his character and showing his connection to mortals.

Book 20: Zeus permits other gods to join the battle, balancing divine intervention between the Greeks and Trojans.

Book 24: Zeus commands Achilles to release Hector’s body for an honorable burial, emphasizing his role as a mediator and upholder of justice.

These scenes illustrate Zeus’s multifaceted role in the Iliad, where he impacts the war’s progress and the fates of key characters. Zeus’s presence permeates the epic through dreams, interventions, and commands. It reflects his status as the king of the gods and his complex ties with mortals and immortals.

Other Myths Involving Zeus

What Was Zeus’s Role in Persephone’s Abduction?

When Hades wanted to marry Persephone, Zeus advised him to abduct her because her mother, Demeter, would not allow the marriage. This narrative is detailed in the “Homeric Hymn to Demeter.”

What Happened in the Orphic “Rhapsodic Theogony”?

In the Orphic “Rhapsodic Theogony” (first century BC/AD), Zeus desired to marry his mother, Rhea. After she refused, Zeus turned into a snake and raped her. Rhea became pregnant and gave birth to Persephone. Zeus, in snake form, mated with Persephone, resulting in the birth of Dionysus.

How Did Zeus Respond to Callirrhoe’s Prayer?

Zeus answered Callirrhoe’s prayer. He sped up the growth of her sons, Acarnan and Amphoterus. They sought revenge for their father Alcmaeon’s death by Phegeus and his sons.

Why Did Thetis Marry a Mortal?

Both Zeus and Poseidon courted Thetis, daughter of Nereus. However, a prophecy by Themis or Prometheus warned that Thetis’s son would be mightier than his father. Thus, Zeus and Poseidon allowed Thetis to marry the mortal Peleus.

Why Did Zeus Kill Asclepius?

Zeus killed Asclepius with a thunderbolt, fearing he would teach resurrection to humans. This act angered Apollo, Asclepius’s father, who killed the Cyclopes that forged the thunderbolts. Zeus planned to imprison Apollo but, at Leto’s request, instead made him serve King Admetus for a year. According to Diodorus Siculus, Hades complained to Zeus because Asclepius’s resurrections diminished the population of the underworld.

What Was Pegasus’s Role in Zeus’s Myths?

The winged horse Pegasus carried Zeus’s thunderbolts.

How Did Zeus Punish Ixion?

Zeus took pity on Ixion, who murdered his father-in-law, and purified him, bringing him to Olympus. However, when Ixion lusted after Hera, Zeus created a cloud resembling Hera (Nephele). Ixion coupled with Nephele, resulting in the birth of Centaurus. Zeus punished Ixion by tying him to a forever-spinning wheel.

What Happened to Phaethon?

Helios allowed his inexperienced son, Phaethon, to drive his chariot. Phaethon lost control, causing destruction. Zeus hurled a thunderbolt at Phaethon to prevent further disaster, killing him and saving the world. In “Dialogues of the Gods” by Lucian, Zeus reprimands Helios for allowing such recklessness.

Various ancient sources, including the “Homeric Hymn to Demeter,” the Orphic “Rhapsodic Theogony,” Diodorus Siculus, and Lucian, tell of Zeus’s interactions and interventions. They provide a rich tapestry of narratives.

Roles and Epithets of Zeus

What Roles Did Zeus Play in Greek Mythology?

Zeus presided over the Greek Olympian pantheon, acting as the king of the gods. He fathered many heroes and featured prominently in their local cults. While Zeus was primarily the god of the sky and thunder, he also embodied Greek religious beliefs and was the archetypal Greek deity.

How Did Local Conceptions of Zeus Differ?

Local varieties of Zeus varied significantly across Greece. For example, some regions worshiped Zeus as a chthonic earth-god rather than a sky deity. Conquest and religious syncretism gradually merged these local gods with the Homeric Zeus. This resulted in various epithets for his different aspects.

What Are Some Key Epithets of Zeus?

These epithets highlighted different facets of Zeus’s authority:

Zeus Aegiduchos or Aegiochos: Known as the bearer of the Aegis, a divine shield with the head of Medusa. Some sources suggest it derives from the goat (αἴξ) and okhē (οχή) referencing his nurse, the divine goat Amalthea.

Zeus Agoraeus (Ἀγοραῖος): Patron of the marketplace (agora) and punisher of dishonest traders.

Zeus Areius (Αρειος): Either “warlike” or “the atoning one.”

Zeus Eleutherios (Ἐλευθέριος): “Zeus the freedom giver,” worshiped in Athens.

Zeus Horkios: Keeper of oaths. Those who broke oaths were made to dedicate a votive statue to Zeus, often at the sanctuary at Olympia.

Zeus Olympios (Ολύμπιος): King of the gods and patron of the Panhellenic Games at Olympia.

Zeus Panhellenios: “Zeus of All the Greeks,” worshipped at Aeacus’s temple on Aegina.

Zeus Xenios (Ξένιος), Philoxenon, or Hospites: Patron of hospitality (xenia) and guests, avenger of wrongs done to strangers.

Sources and Further Reading

According to “The Theogony” by Hesiod (lines 886–900), Zeus’s first wife was Metis, one of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys.

Apollodorus provides detailed accounts of the Gigantomachy and other myths involving Zeus in his work “Library.”

Homer’s “Iliad” includes numerous references to Zeus’s roles and interventions in human affairs.

Zeus’s epithets and roles reflect the complexity and depth of his character in Greek mythology. He was a multifaceted deity whose influence spanned various aspects of life and the cosmos.

Panhellenic Cults of Zeus

What Were the Major Centers of Zeus Worship?

The major center where Greeks converged to honor Zeus was Olympia. This location hosted the famous quadrennial festival featuring the Olympic Games. Notably, the altar to Zeus at Olympia was made not of stone, but of ash, accumulated from centuries of animal sacrifices.

How Did the Worship of Zeus Vary Across Greece?

Outside major sanctuaries, worship practices for Zeus varied widely across the Greek world. For example, sacrificing a white animal over a raised altar was a common ritual. However, specific titles and modes of worship could differ from Asia Minor to Sicily.

What is Zeus Velchanos?

Most Greeks recognized Crete as the birthplace of Zeus. Minoan culture, which greatly influenced Greek religion, contributed the idea of “Zeus Velchanos” or “boy-Zeus.”” This youthful deity, often simply called Kouros, was worshipped in various Cretan caves such as Knossos, Ida, and Palaikastro. Hellenistic coins from Phaistos depict Velchanos in two ways. One shows him as a youth with a cockerel on his knee. The other shows him as an eagle, linked to a goddess in a mystic marriage.

How Was Zeus Worshiped in Crete?

In Crete, Zeus was represented as a long-haired youth and celebrated as “ho megas kouros” or “the great youth.” Inscriptions at Gortyn and Lyttos record a festival, the Velchania. It shows a widespread veneration in Hellenistic Crete. Plato’s Laws emphasizes the archaic Cretan knowledge along the pilgrimage route to such sites.

What Are the Myths and Artifacts Related to Cretan Zeus?

The myth of Cretan Zeus’s death, mentioned by Callimachus and supported by Antoninus Liberalis, suggests an annual vegetative spirit. Sir Arthur Evans found ivory statuettes of the “Divine Boy” near the Labyrinth at Knossos. They emphasize Zeus’s youthful form. Euhemerus proposed that Zeus was originally a great king of Crete whose glory posthumously turned him into a deity, an idea later taken up by Christian writers.

Sources and Further Reading

Will Durant’s The Story of Civilization describes the influence of Minoan culture on Greek religion.

Callimachus, in his hymn, and Antoninus Liberalis provide accounts of the myth of Cretan Zeus.

Plato’s Laws highlights the significance of Cretan religious sites.

Sir Arthur Evans’s archaeological findings at Knossos offer insights into the worship of Zeus Velchanos.

What Is Zeus Lykaios and the Lykaia Festival?

Zeus Lykaios, meaning “Wolf-Zeus,” is an epithet of Zeus associated with the ancient festival of the Lykaia. This festival took place on the slopes of Mount Lykaion, the tallest peak in Arcadia. The Lykaia’s archaic rituals included primitive rites of passage. They threatened cannibalism and possible werewolf transformation for the young men (ephebes) who participated.

What Were the Rituals and Myths of the Lykaia?

A particular clan would gather every nine years on Mount Lykaion to make a sacrifice to Zeus Lykaios. During this ritual, a piece of human entrails would be mixed with the animal sacrifice. According to Plato’s Republic (Book 8, 565d-566a), those who ate human flesh would turn into wolves. They could regain their human form only by not eating human flesh for nine years.

What Is the Significance of the Name Lykaios?

The name Lykaios or Lykeios, attributed to both Zeus and Apollo, may derive from the Proto-Greek λύκη, meaning “light.” Achaeus, a contemporary tragedian of Sophocles, referred to Zeus Lykaios as “starry-eyed.” Cicero described the Arcadian Zeus as the son of Aether in De Natura Deorum (Book 3, Chapter 21). Pausanias noted that the altar of Zeus on Mount Lykaion had columns with gilded eagles facing the sunrise. This reinforced the light association in his Description of Greece (8.2.1).

What Did the Rituals Involve?

The Lykaia rituals took place near an ancient ash-heap where sacrifices occurred. A forbidden precinct nearby allegedly cast no shadows, adding to the mystical nature of the rites. This shadowless precinct might symbolize Zeus as the “god of light” (Lykaios).

Additional Cults

Although Zeus was originally a sky god, many Greek cities honored local versions of Zeus who lived underground. Athenians and Sicilians worshipped Zeus Meilichios (“kindly” or “honeyed”). Other cities honored Zeus Chthonios (“earthy”), Zeus Katachthonios (“under-the-earth”), and Zeus Plousios (“wealth-bringing”). These deities were often represented as snakes or in human form in visual art, or even as both together. They received offerings of black animal victims sacrificed in sunken pits. This was similar to the worship of chthonic deities like Persephone and Demeter, and to heroes at their tombs. Olympian gods, in contrast, usually received white victims sacrificed on raised altars.

In some cases, cities were uncertain whether the entity they sacrificed to was a hero or an underground Zeus. The shrine at Lebadaea in Boeotia might belong to either the hero Trophonius or Zeus Trephonius (“the nurturing”). It depends on whether you believe Pausanias (Description of Greece, 9.39.5) or Strabo (Geography, 9.2.38). The hero Amphiaraus was honored as Zeus Amphiaraus at Oropus outside of Thebes, and the Spartans even had a shrine to Zeus Agamemnon. The ancient Molossian kings sacrificed to Zeus Areius. Strabo mentions that at Tralles, there was a cult of Zeus Larisaeus (Geography, 14.1.42). In Ithome, they honored Zeus Ithomatas with a sanctuary, a statue, and an annual festival called Ithomaea (Pausanias, 4.33.2).

Hecatomphonia

Hecatomphonia (ἑκατομφόνια) was a custom among the Messenians. They offered a sacrifice to Zeus when anyone had killed a hundred enemies. Aristomenes offered this sacrifice three times during the Messenian Wars against Sparta (Pausanias, 4.17.6; Diodorus Siculus, 15.66).

Non-Panhellenic Cults

In addition to the Panhellenic titles and conceptions of Zeus, local cults maintained their own unique ideas about the king of gods and men. As Zeus Aetnaeus, he was worshipped on Mount Aetna, where there was a statue of him and a local festival called the Aetnaea in his honor (Pindar, Pythian Odes, 1.10). Another example is Zeus Aeneius or Zeus Aenesius (Αἰνησιος), worshipped on the island of Cephalonia, where he had a temple on Mount Aenos (Strabo, 10.2.15).

Oracles

Although most oracular sites were dedicated to Apollo, heroes, or goddesses like Themis, a few were dedicated to Zeus. Foreign oracles, such as Baʿal’s at Heliopolis, were also associated with Zeus in Greek or Jupiter in Latin.

The Oracle at Dodona

The cult of Zeus at Dodona in Epirus dates back to the second millennium BC. This oracle centered on a sacred oak tree. Homer’s Odyssey (circa 750 BC) says that barefoot priests called Selloi performed divinations. They did this by observing the rustling leaves and branches of an oak (Odyssey 14.327-330). By the time of Herodotus, female priestesses called peleiades (“doves”) had replaced the male priests (Histories 2.55).

At Dodona, Zeus’s consort was not Hera but the goddess Dione. Dione’s name is a feminine form of “Zeus.” Her status as a titaness suggests she was a powerful, pre-Hellenic deity. She may have been the original occupant of the oracle (Hesiod, Theogony 353-370).

The Oracle at Siwa

The oracle of Ammon at the Siwa Oasis in Egypt was outside the Greek world before Alexander the Great, but it was well-known during the archaic era. Herodotus mentions consultations with Zeus Ammon in his account of the Persian War (Histories 2.54). Zeus Ammon was particularly favored in Sparta, where a temple to him existed by the time of the Peloponnesian War (Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 2.54).

Alexander the Great famously consulted the oracle at Siwa. This event sparked the Hellenistic imagination, contributing to the figure of a Libyan Sibyl (Plutarch, Alexander 27.8).

Other Cults

Although etymology indicates Zeus was originally a sky god, many Greek cities honored local versions of Zeus who lived underground. Athenians and Sicilians honored Zeus Meilichios (“kindly”). Other cities had Zeus Chthonios (“earthy”), Zeus Katachthonios (“under-the-earth”), and Zeus Plousios (“wealth-bringing”). These deities were often represented as snakes or in human form, or even as both. They received offerings of black animal victims, sacrificed in sunken pits. This was similar to chthonic deities like Persephone and Demeter, and heroes at their tombs (Pausanias, Description of Greece 1.24.4).

In some cases, cities were uncertain whether they were sacrificing to a hero or an underground Zeus. For example, the shrine at Lebadaea in Boeotia might belong to the hero Trophonius or to Zeus Trephonius (“the nurturing”), depending on whether you believe Pausanias (Description of Greece 9.39.5) or Strabo (Geography 9.2.38). The hero Amphiaraus was honored as Zeus Amphiaraus at Oropus, and the Spartans had a shrine to Zeus Agamemnon (Strabo, Geography 13.1.30).

Hecatomphonia

Hecatomphonia was a custom among the Messenians where they offered a sacrifice to Zeus when any of them had killed a hundred enemies. Aristomenes performed this sacrifice three times during the Messenian Wars against Sparta (Pausanias, Description of Greece 4.17.6; Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 15.66).

Non-Panhellenic Cults

Zeus was also worshipped in various local forms outside the main Panhellenic cults. As Zeus Aetnaeus, he was worshipped on Mount Aetna with a statue and a local festival called the Aetnaea (Pindar, Pythian Odes 1.10). On the island of Cephalonia, he was worshipped as Zeus Aeneius or Zeus Aenesius, with a temple on Mount Aenos (Strabo, Geography 10.2.15).

Identifications with Other Gods

Foreign Gods

Zeus was identified with the Roman god Jupiter and syncretized with other deities, such as the Egyptian Ammon and the Etruscan Tinia. In Rome, he and Dionysus absorbed the role of the chief Phrygian god Sabazios, forming the syncretic deity known as Sabazius. The Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV Epiphanes erected a statue of Zeus Olympios in the Judean Temple in Jerusalem. Hellenizing Jews called it Baal Shamen (Lord of Heaven). Zeus is also identified with the Hindu deity Indra due to their similar roles as kings of gods and wielders of thunderbolts.

Helios

Zeus is occasionally conflated with the Hellenic sun god, Helios, who is sometimes directly referred to as Zeus’s eye or implied as such. Hesiod, for instance, describes Zeus’s eye as the sun. This perception might derive from earlier Proto-Indo-European religion, where the sun is envisioned as the eye of *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr. Euripides described Zeus as “sun-eyed” in his now-lost tragedy Mysians, and Helios is referred to as “the brilliant eye of Zeus, giver of life.” In Euripides’s Medea, the chorus calls Helios “light born from Zeus.”

The connection of Helios to Zeus has many examples of direct identification in later times. In the Hellenistic period, a Greco-Egyptian god, Serapis, was born. He was a chthonic avatar of Zeus, often shown with solar traits. Joint dedications to “Zeus-Serapis-Helios” were common across the Mediterranean. The Anastasy papyrus equates Helios to Zeus, Serapis, and Mithras. Inscriptions from Trachonitis mention “Zeus the Unconquered Sun.” A lacunose inscription on Amorgos, an Aegean island, reads Ζεὺς Ἥλ[ιο]ς (Zeus the Sun). It suggests early sun elements in Zeus’s worship by the fifth century BC. The Cretan Zeus Tallaios also had solar elements in his cult, with “Talos” being the local equivalent of Helios.

Later Representations

Philosophy

In Neoplatonism, Zeus is equated with the Demiurge or Divine Mind, especially within Plotinus’s Enneads and Proclus’s Platonic Theology.

The Bible

Zeus appears in the New Testament twice. In Acts 14:8-13, the people of Lystra identified the Apostle Paul with Hermes and Barnabas with Zeus after witnessing Paul heal a lame man. Inscriptions near Lystra mention “priests of Zeus” and refer to “Hermes Most Great” and “Zeus the sun-god.” In Acts 28:11, the ship carrying Paul bore the figurehead “Sons of Zeus” (Castor and Pollux).

The deuterocanonical book of 2 Maccabees 6:1-2 describes King Antiochus IV Epiphanes’s attempt to stamp out Jewish religion by rededicating the Jerusalem temple to Zeus Olympius.

Additional Cults

Though Zeus was originally a sky god, many Greek cities honored local versions of him as an underground deity. Athenians and Sicilians honored Zeus Meilichios (“kindly” or “honeyed”). Other cities had Zeus Chthonios (“earthy”), Zeus Katachthonios (“under-the-earth”), and Zeus Plousios (“wealth-bringing”). These deities were represented as snakes, humans, or both. They received sacrifices of black animal victims, like those for chthonic deities such as Persephone and Demeter【Pausanias, Description of Greece, 1.24.4】.

In some cases, cities were uncertain if they were sacrificing to a hero or an underground Zeus. The shrine at Lebadaea in Boeotia could belong to the hero Trophonius or to Zeus Trephonius (“the nurturing”)【Pausanias, Description of Greece, 9.39.5】【Strabo, Geography, 9.2.38】. The hero Amphiaraus was honored as Zeus Amphiaraus at Oropus, and the Spartans had a shrine to Zeus Agamemnon【Strabo, Geography, 13.1.30】. Molossian kings sacrificed to Zeus Areius, and Strabo mentions Zeus Larisaeus at Tralles. In Ithome, Zeus Ithomatas had a sanctuary and an annual festival in his honor called Ithomaea【Strabo, Geography, 10.2.15】.

Hecatomphonia

Hecatomphonia, meaning “killing of a hundred,” was a Messenian custom of offering sacrifices to Zeus after killing a hundred enemies. Aristomenes performed this sacrifice three times during the Messenian Wars against Sparta【Pausanias, Description of Greece, 4.17.6】【Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, 15.66】.

Non-Panhellenic Cults

Zeus was worshipped in various local forms outside the main Panhellenic cults. As Zeus Aetnaeus, he was honored on Mount Aetna with a statue and a local festival called the Aetnaea (Pindar, Pythian Odes, 1.10). On the island of Cephalonia, he was worshipped as Zeus Aeneius, with a temple on Mount Aenos (Strabo, Geography, 10.2.15).

Oracles

The Oracle at Dodona

The cult of Zeus at Dodona in Epirus dates back to the second millennium BC. According to Homer’s Odyssey (14.327-330), barefoot priests called Selloi performed divinations by observing the rustling leaves of a sacred oak tree. By Herodotus’s time, female priestesses called peleiades (“doves”) had replaced the male priests【Herodotus, Histories, 2.55】. At Dodona, Zeus’s consort was Dione, whose name is a feminine form of “Zeus”【Hesiod, Theogony, 353-370】.

The Oracle at Siwa

The oracle of Ammon at the Siwa Oasis in Egypt was outside the Greek world before Alexander the Great. Herodotus mentions consultations with Zeus Ammon in his account of the Persian War【Herodotus, Histories, 2.54】. Zeus Ammon was favored in Sparta, where a temple to him existed by the Peloponnesian War【Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 2.54】. Alexander sought guidance from the Siwa oracle, shaping a Libyan Sibyl image.

Before you buy tickets, read the guide for 2024. Click Here

Before you buy tickets, read the guide for 2024. Click Here