The

Learn all about the

Choose your favorite platform and purchase tickets for archaeological sites in Greece. Experience the rich history and beauty of ancient wonders.

Combo Ticket:

Acropolis and 6 Archaeological Sites from 36€

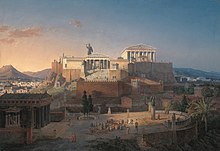

The Acropolis of Athens is an ancient citadel located on a rocky outcrop above the city of Athens and contains the remains of several ancient buildings of great architectural and historic significance, the most famous being the Parthenon.

Acropolis and 6 Archaeological Sites Combo Ticket

Acropolis and 6 Archaeological Sites Combo Ticket

- Skip-the-line

- Free cancellation.

Acropolis of Athens – Athens Greece

The

Here, the iconic Parthenon stands, a testament to the brilliance of classical architecture. Walking through these ancient ruins, you feel the whispers. They are of philosophers and playwrights echoing through the ages.

The

Athens Acropolis , Greece: A Story of Ancient Beauty

Introduction

The

The Start of the Acropolis

The

The Parthenon: A Beautiful Temple

The best part of the

The Parthenon’s Art

The Parthenon’s beauty isn’t just its look. It has carvings that tell stories. They show gods and other tales. These are not just pretty. They tell us about old Greek life.

More Than the Parthenon

There’s more to see than just the Parthenon. The Erechtheion has statues of women as pillars. The Propylaea is a big gate. It’s the first thing people see when they come.

Many Years of the Acropolis

The

The Official Ticketing Site for Acropolis Tickets online | GUIDE 2024

The Official Ticketing Site for Acropolis Tickets online | GUIDE 2024

Before Purchasing from the official website of the Greek government Please Note

Myths of the Acropolis

The

Visiting the Acropolis Now

Many people visit the

Life in Ancient Athens

The

The Theater of Dionysus

Near the

The Museum of the Acropolis

There’s a museum for the

Greek Gods and the Acropolis

The

The Acropolis During Wars

The

Olive Trees and Athena

The olive tree is a symbol of Athens. It comes from a story about Athena. She gave an olive tree as a gift. This tree meant peace and wealth for Athens.

Walking Around the Acropolis

Walking around the

The Importance of the Acropolis

The

The Colors of the Acropolis

In ancient times, the

The Acropolis at Night

At night, the

Festivals at the Acropolis

The Greeks had festivals here. These were big events with music, dancing, and food. They celebrated their gods and life. The

The Restoration of the Acropolis

Today, people work to keep the

The Acropolis in Modern Culture

The

Learning from the Acropolis

The

The Global Impact of the Acropolis

The

Conclusion

The Athens

The Stones of the Acropolis

The stones of the

Learning at the Acropolis

The

Myths and Legends Around the Acropolis

There are so many stories about the

Nature Near the Acropolis

Around the

Greek Design in Buildings Everywhere

The

The Acropolis in Art and Books

Lots of artists and writers get ideas from the

A Symbol of People Power

The

The Acropolis and Greek Pride

For Greek people, the

Visiting the Acropolis : Tips and Thoughts

Visiting the

The View from the Acropolis

The view from the

The Acropolis in the Evening

Seeing the

Festivals and Events

The

Preserving the Acropolis

Today, people work hard to keep the

The Acropolis in Movies and Media

The

Why the Acropolis Matters

The

Conclusion: A Must-See Wonder

The Athens

See also: Pay 1/3 the price to see all the sights of Athens. Updated Guide for 2024

CLICK HERE 👇

Athens Acropolis Greece

- Plan your visit: Research the site and its history, check the opening hours and availability of tickets, and plan your route to the

Acropolis . - Dress appropriately: Wear comfortable shoes and clothing covering your shoulders and legs, as revealing clothing is prohibited.

- Bring water and sun protection: The

Acropolis is located on a hill and the walk up can be steep, and the heat can be intense during the summer months. - Go early or late: To avoid the crowds, try to visit the

Acropolis early in the morning or later in the afternoon. - Take a guided tour: Guided tours can provide valuable insight into the history and significance of the site.

- Be respectful: The

Acropolis is a sacred site, so be sure to behave appropriately and respect the ancient structures. - Check for restrictions or precautions due to the COVID-19 pandemic: The Greek Ministry of Culture and Sport website may have specific protocols in place, so be sure to check for updates before your visit.

- Bring a camera: The views of the city and the ancient structures are beautiful and worth capturing.

- Enjoy the visit, the

Acropolis of Athens is one of the most famous and historically important sites in the world, and a visit will be an unforgettable experience.

Quick Links to tickets for the

► Skip-the-line tickets can be purchased online via GetYourGuide Click HERE <- (includes free cancellation)

Or Tiqets Click HERE <- (does not include free cancellation).

Viator Click Here (includes free cancellation)

► A popular combination is Entry tickets to both the

Here are some questions you may have about the Acropolis of Athens:

From October 1st to March 31st:

- Monday: 8:00 am – 5:00 pm

- Tuesday: closed

- Wednesday: 8:00 am – 5:00 pm

- Thursday: 8:00 am – 5:00 pm

- Friday: 8:00 am – 5:00 pm

- Saturday: 8:00 am – 5:00 pm

- Sunday: 8:00 am – 5:00 pm

From April 1st to September 30th:

- Monday: 8:00 am – 8:00 pm

- Tuesday: closed

- Wednesday: 8:00 am – 8:00 pm

- Thursday: 8:00 am – 8:00 pm

- Friday: 8:00 am – 8:00 pm

- Saturday: 8:00 am – 8:00 pm

- Sunday: 8:00 am – 8:00 pm

Check the official website of the

How long does it take to visit the Acropolis ?

The time to visit the

But, if you like ancient Greek history and culture and want to explore the site, you may want to allow more time for your visit. Additionally, if you are taking a guided tour, the time may vary.

You should check the official website of the

How much does it cost to visit the Acropolis ?

The cost to visit the

As of 2024:

- Full-price ticket for the

Acropolis : 20€ - Reduced-price ticket for the

Acropolis (for students and senior citizens): 10€ - Free admission for European Union citizens under 18 and over 65 years old.

Some tours that include the

It’s recommended to check the official website of the

Please note that the prices may be different during the COVID-19 pandemic and it’s always better to check with the official website for any updates.

Is there a guided tour available at the Acropolis ?

Yes, there are guided tours available at the Acropolis. Visitors can take a guided tour of the site to learn more about the history and significance of the ancient structures. Guided tours can be a great way to gain a deeper understanding of the site and the culture of ancient Greece.

You can book a guided tour with an authorized tour operator or a local tour agency. They usually offer a variety of tour options, such as group tours, private tours, and audio tours. They can also offer tours in different languages.

-

You should check the official website of the

Acropolis or the Greek Ministry of Culture. They have updates on tours. They may change due to COVID-19.

Also, you can visit the

The Acropolis

The word

Pericles (c. 495-429 BC) inhabited the hill as far back as the fourth millennium BC, and there is evidence to support this. He lived from 495 – 429 BC. He coordinated the construction of the site’s most important present remains. These include the Parthenon, the Propylaia, the Erechtheion, and the Temple of Athena Nike. The Venetians damaged the Parthenon and other buildings. This happened during the 1687 siege in the Morean War. A cannonball hit and exploded gunpowder stored in the Parthenon.

What item of clothing does the Acropolis of Athens ban?

Visitors to the

You must wear shirts and shoes at all times. You can’t wear revealing clothing like tank tops, shorts, and miniskirts.

-

Additionally, the ban includes clothing that is disrespectful or offensive. This includes clothes with offensive language or images.

-

Visitors should also know this. During the hot summer, they should wear light, comfy clothes. They should also wear shoes with good support. The walk up is steep and the heat is intense.

Also, check for extra COVID-19 restrictions on the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sport website. They might have specific rules.

Where is the Acropolis of Athens located?

Are there any special requirements to enter the Acropolis ?

No rules keep you out of the

-

Visitors must dress and wear shirts and shoes at all times. Revealing tank tops, shorts, and miniskirts are not permitted.

-

Respect the

Acropolis . It holds sacredness. So, visitors should behave well and respect the old structures. -

Visitors can take photos in the

Acropolis . But, they can’t use flash. -

Food and drinks: Eating and drinking are not allowed inside the

Acropolis . -

Luggage: Large bags and backpacks are not allowed inside the

Acropolis . You can leave them in the cloakroom near the entrance or at your hotel. -

COVID-19: Visitors must wear masks. They must keep their distance. They must follow extra guidelines and rules due to the pandemic.

You should check the official website of the

Also, the

Acropolis of Athens Early settlement

The

Archaeological evidence suggests that the first people lived in Attica. They lived there in the Early Neolithic period (6th millennium BC). Late Bronze Age Mycenean megaron palaces were almost here.

-

Only a single limestone column base remains. We also have fragments of many sandstone steps from this megaron. After the palace, they built a huge circuit wall. It was Cyclopean, 760 meters long, up to 10 meters high, and 3.5 to 6 meters thick.

-

Until the fifth century, this wall was the

acropolis ‘ primary line of defence. -

The wall had two parapets. The workers bonded big stone blocks with Templeton, an earth mortar. This is typical of Mycenaean design. They positioned the wall’s southern entrance. It had a parapet and tower hanging over the intruders’ right side. This made defense much easier.

House of Erechtheus

On the north side of the hill, there were two more modest ascent routes comprised of narrow, steep stairs dug into the rock. The “strong-built House of Erechtheus” (Odyssey 7.81) is thought to be a reference to this stronghold.

A fracture formed on the northeastern border of the

No substantial evidence exists for the presence of a Mycenean palace on top of the

Archaic Acropolis

Proposed elevation of the Old Temple of Athena. Built around 525 BC, it stood between the Parthenon and the Erechtheum. Fragments of the sculptures in its pediments are in the

-

We know little about the

Acropolis ‘ architectural appearance until the Archaic period. For a brief period in the 7th and 6th century BC, Kylon held the location. He tried to seize government by a coup d’état. Peisistratos also held it. -

Later, Peisistratos referenced the entrance gate or Propylaea that he had erected.

-

The Enneapylon protected the Clepsydra spring as a result. The spring is at the northern foot of the Enneapylon.

The residents of the city built a temple in 570-550 BC to honour their tutelary goddess, Athena Polias. This is after the pedimental three-bodied man-serpent sculpture. Someone painted its beards dark blue. It is also called the Bluebeard Temple. This is after the three-headed pedimental man-serpent sculpture. It’s not clear whether this temple is a new one, or only a holy precinct or altar. The builders may have erected the Hekatompedon on the site of the Parthenon.

Arkhaios Nes

The Peisistratids built another temple from 529 to 520 BC. They called it the Arkhaios Nes (v, “old temple”). They used the Dörpfeld foundations to build this temple. It sits between the Erechtheion and the still-standing Parthenon. The Persian invasion destroyed Arkhaios Nes in 480 BC. But, the temple was likely repaired in 454 BC. The Delian League moved its treasury to the temple’s opisthodomos. They reconstructed the temple during this time. A fire may have destroyed the temple around 406/405 BC. Xenophon records a fire at the old Athena temple. In his second-century AD Description of Greece, Pausanias makes no mention of it.

-

In 500 BC, they destroyed the Hekatompedon to make way for the “Older Parthenon,” or “early Parthenon.” They built the Older Parthenon from Piraeus limestone. The stone was for the Olympieion temple. The tyrannical Peisistratos and his sons were linked to it. To make the summit level, workers added about 8,000 two-ton limestone slabs to the south side. They built a foundation 11 meters (36 feet) deep and filled it with dirt, which they held in place with a retaining wall.

-

After the victory at Marathon in 490 BC, they implemented a new strategy. Someone swapped in marble. Pre-Parthenon I refers to the limestone period. Pre-Parthenon II refers to the marble phase. They halted construction in 485 BC. Xerxes became king of Persia and war seemed imminent. The halt was to save resources. The Persians came and plundered Athens in 480 BC. They were still building the Older Parthenon. A fire and looting destroyed the temple and almost all its contents.

The Persian crisis ended.

Then, the Athenians put parts of the incomplete temple on the new northern wall of the

The Periclean Building Program

They ordered a renovation of the

A colossal gate at the western extremity of the

- In 432 BC, the northern wing of these colonnades, which had paintings by Polygnotus, was almost complete.

- Small Pentelic marble temples of Pentelic marble, with tetrastyle porches, were also being built south of the Propylaea at the same time as the Athena Nike Temple. After the Peloponnesian War, the temple was completed between 421 BC and 409 BC under Nicias’ peace.

They built the temple from 421–406 BC. Its site had uneven terrain and many nearby shrines. So, builders used complex plans to avoid them.

-

Six Ionic columns flank the east-facing entryway. The temple has two porches. One is on the northwest corner. Ionic columns support it. The other is on the southwest corner. Enormous female statues called Caryatids support it.

-

They dedicated it to Athena Polias. The eastern section of the temple featured the altars of Hephaestus and Voutos. Voutos was the brother of Poseidon-Erechtheus. The altars served the worship of the archaic ruler. Fire destroyed the original interior design in the first century BC. It was then rebuilt many times. The original design is unknown.

At the same time, they built the Kore Porch (Porch of the Maidens) or Caryatids’ balcony. It included the temples of Athena Polias and Poseidon. It also included the temples of Erechtheus, Cecrops, Herse, Pandrosos, and Aglauros.

The Sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia was near the Athena Nike and the Parthenon. In the deme of Brauron, the people worshipped Artemis, who appeared as a bear. In the shrine, according to Pausanias, a wooden statue of the goddess was there. Also, a statue of Artemis was there. Praxiteles built it in the 4th century BC.

When Phidias’ enormous bronze statue of Athena Promachos (Athens who battles in the front line) stood beside the Propylaea in Athens, it had a resounding presence.

There was a 1.50-meter (4-foot-11-inch) height difference between the statue’s base and its full 9-meter (30-foot) height. The crews of ships crossing Cape Sounion could see the golden point of the goddess’ spear and a massive shield on her left side, adorned by Mys with scenes of the Centaur-Lapith battle. [28] The Chalkotheke, the Pandroseion, the sanctuary of Pandion, the altar of Athena, the sanctuary of Zeus Polieus, and the circular temple of Augustus and Rome from Roman times are other sites that have almost nothing remaining to be seen today.

Hellenistic and Roman period

The renovation of many structures around the

-

Eumenes also built a stoa on the South slope of the Agora, like that of Attalos.

-

The Parthenon is about 23 meters away. A modest, round temple was the last ancient structure on this rock’s top. They built it during the Julio-Claudian era. They called it the Temple of Rome and Augustus.

They built another sanctuary on the North slope. Since classical times, people devoted the location near the one to Pan. In it, the archons consecrated Apollo upon taking office.

The Roman Herodes Atticus built his huge amphitheatre, called an Odeon, on the South slope. He did this around 161 AD. They finished Reconstruction in the 1950s. Then the Herulians invaded a century later, but they destroyed it.

In the third century, they fortified the walls against a Herulian invasion. This involved building the “Beulé Gate,” which blocked entry in front of the Propylaia.

Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman period

Throughout the Byzantine era, the Parthenon’s church venerated the Virgin Mary. The

The Ottomans invaded Greece. After that, they turned the Parthenon and Erechtheum into the private harems of their governors. Venetians besieged Athens in 1687 during the Morean War. The damage affected the

Leo von Klenze, 1846, idealized the restoration of the Acropolis and Areios Pagos in Athens.

Byzantine, Frankish and Ottoman constructions occupied the

Acropolis of Athens – Archaeological remains

Ascending to the

The

Acropolis of Athens – Site plan

Site plan of the

The Acropolis of Athens Restoration Project

In the summer of 2014, this view faced east toward the

The Project started in 1975, but it has come to a grinding stop by 2017. The purpose was to reverse centuries of decay, pollution, destruction, and wrong restorations. Collectors collected even tiny stone pieces from the

-

New marble from Mount Penteli was also used. It helped recreate as much of the

Acropolis ‘ original material as possible (anastylosis). If a new team makes changes, the titanium dowels in the restoration will allow for a smooth switch. They paired the latest technology with a long study. They also reinvented traditional methods. -

As a result, the 17th-century Venetian assault damaged the Parthenon colonnades. They corrected several built columns. Workers have repaired some of the Propylaea’s roof and floor. They used fresh marble for parts and added blue and gold inlays, like the original. The restoration of the Temple of Athena Nike to its former glory took place in 2010.

They used shards of the originals to make 686 stones. They mended 905 with new marble. The restoration used 186 new marble sections to finish, weighing a total of 2,675 tons. They used a total of 530 cubic meters of brand-new Pentelic marble in this project.

Before you buy tickets, read the guide for 2024. Click Here

Before you buy tickets, read the guide for 2024. Click Here